| Monday, April 24

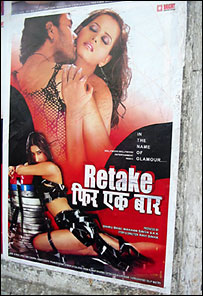

There were posters for some other films outside the movie hall, including "Free Entry" a pun on a recent popular film called "No Entry," which was about some swinging young couples. There was also "Bad Girl" -- the poster had a girl in a miniskirt dancing, with a large red cross stamped on her. I went back a week or so later and found posters for "Madhubala" and "Free Entry" gone, while a large white poster had been stuck over "Bad Girl." the sign advertising its earlier shows and another that said "Strictly Over 18" were still visible. I wondered if the moral police and I were on some telepathic wave-length, but the boy at the cigarette and telephone stand under the poster said the movie hall had been booked for two weeks by schools so kids could watch the pariotic flick "Rang de Basanti" (Color Me Saffron). For the cinema's regular clients, something called "Retake: One More time " was on offer.

My heart sank. The DDA is the largest land-owning body in the city and is also responsible for the 20-year "master plans" that are supposed to govern how the city develops. They are still working on the master plan for 2000-2021. It is expected later this year though this no doubt has been said for the last six years. More to the point, They are housed in a tall, depressing building (see a photo in August 2005 in the archives) and my modus operandi of looking up a bureaucrat's name on the Internet and then hanging around outside their office trying to ingratiate myself with their peons seemed unlikely to work there. The DDA is, I'm sure, By Appoinment Only. Well, I supposed I could call up and ask for an appointment on some seemingly innocuous topic: the Beautification of World-Class Delhi, say. Or should it be the World-Classification of Beautiful Delhi?

It was six o'clock. The office was closed. I tried to go to the DDA last week but it was Friday and everything was closed for Easter. So I went back to Nangla Machi.

A group of people who ran a cyber house there started a listserve for people who had an association with the neighborhood, I think some are residents, I'm not sure about all. The listserves are both in English and Hindi, though with roman text. In the darkened house of one of Nangla's leaders, surprising cool and with incense to keep away the mosquitoes, four or five men amassed papers showing proof of tenure in the city -- ration cards, election cards. I spoke a while to the man organizing these efforts. In the middle one of his men interrupted, anguished. "People who came from other places, from what is now Pakistan, not even India, they got land," he said. "What about us, we were born in a free India. Where is our land?" saying it don't make it so

Open drains run past one of the poshest neighborhoods in South Delhi -- Panchsheel Park. And they border Siri Fort Auditorium -- a theater that is part of the Asian Games complex, built the last time India was trying to impress its friends and neighbors by hosting an international athletic event (the next ones are the Comomonwealth Games, 2010). Still, I can't help but wonder how these drains -- which I can adjust to but not really warm to -- figure into the cityscape of all those who insist on linking the following three words: world, class, Delhi. I couldn't juxtapose the two together any better than the Times of India has just done with its new advertising campaign. (You can't see it but Siri Fort is right behind.) Monday, April 2

To be accurate, there were three mentions of it. NDTV did a feature (well done Poonam Aggarwal, the reporter who did it) interviewing a woman who lived there. The Indian Express ran a photo (which my illustration is copied from). And Navbharat Times, a Hindi daily, did a story about how protesting slum dwellers had snarled traffic on bridges leading from the city to across the river.

Some of them had been there for 20 years, some for 15. One of them, close to the main road, had added a second floor to his shack and painted the whole thing blue. Passing it the other evening, my mother said, "I thought that one was asking for trouble." But strangely, it's one of the ones still standing. I visited them on my way home from work Friday. They were sort of expecting me, or someone from the news anyway -- they had been keeping tabs of how their turmoil of the last week had been covered and they weren't very pleased. One woman said to me, "It's great fun for you isn't it? To come here and have a look around?" I felt stung but I couldn't argue with her. No one can be expected to like a tourist, especially when your house has just been torn down. I am reading a book about the late 1970s, when under a two-year dictatorship the then prime minister had had parts of the city torn down and shifted their residents elsewhere. The elsewhere to where they were moved to was the wilds of the city then, but I realize from looking up the names from the map that we live squarely among the “resettlements.” But now some of the resettlements are being torn down as well. Since a court judgment in November 2002, the city's slum department has been going after all the people living on the river banks in order to, what else, beautify the city. And now, the city doesn't owe any alternate housing to people who moved here after 1998. Those who moved before 1990 will get a 25 square meter plot, supposedly, those who moved between 1990 and 1998 will get 12.5 square meters. How big is that? I'll have to lay newspapers end to end and measure them to see how many papers make a house of that size. I wanted to visit some of ones near our house as well -- partly because one of them, I think, is mentioned in the book through which I first mentally registered the Emergency city beautification campaign. And because people who work for us live there. But even though some of the neighborhoods – Ambedkhar Camp, Khichripur (which I believe is where our hero gets removed to in "Midnight's Children" but I have to check that. Loosely translated, it means Goulashville, which I think can't be accidental) – are less than a mile away I haven’t managed to get myself there. Somehow everytime I think about going there, I feel this loathness to actually go. Honestly, I think it’s a reluctance to leave the psychological safety of my class confines. People will justifiably look at me strangely or mistake me for a city employee and ask me questions I have no answers to. But Nangli

Machi was on my way home, the demolition had just happenend, no one

was writing about it and if I didn’t go soon, except for the

two words and few lines in my Eicher map, they would be gone. That's

what happened to Rajeev Camp, around the corner, which was broken

down a month after we moved here. I couldn't find it on the map the

other day -- there isn't even that evidence now that it existed. When

things you know were there aren't on maps it's sort of a vertiginous

feeling. The movie-influenced part of my mind can't help wonderng:

was it never on page 102 to begin with, or did it melt away later? |

Two

weeks ago I was walking around the middle circle of Connaught Place

to go to a cotton clothing store on the other side from where my office

is located. I passed the red tall building that houses Citibank, with

Pallika Bazaar (home of portable telephone sets and pirated DVDs)

on my right. As I passed the radial street that leads off the circe

to The Shop (yet another one of the many vegetable dye cotton stores)

I saw a poster with a pretty girl on it and the word "Madhubala" emblazoned

on it in large letters. I was intrigued -- I was wondering if it was

perhaps a biopic of the classic Bollywood starlet, but the girl looked

rather modern and slightly dressed. I got to the poster and to my

shock and horror read this: "She was raped 21 times. Find out how...".

Two

weeks ago I was walking around the middle circle of Connaught Place

to go to a cotton clothing store on the other side from where my office

is located. I passed the red tall building that houses Citibank, with

Pallika Bazaar (home of portable telephone sets and pirated DVDs)

on my right. As I passed the radial street that leads off the circe

to The Shop (yet another one of the many vegetable dye cotton stores)

I saw a poster with a pretty girl on it and the word "Madhubala" emblazoned

on it in large letters. I was intrigued -- I was wondering if it was

perhaps a biopic of the classic Bollywood starlet, but the girl looked

rather modern and slightly dressed. I got to the poster and to my

shock and horror read this: "She was raped 21 times. Find out how...".

The

poster really bothered me a lot, even though I think (though now I

wonder about that) that violent or sexual crime isn't driven by watching

violent or sexually graphic television or movies. All sorts of plots

drive x-rated movies -- and hey, it's just fantasy, right? Maybe in

some other place (Sweden?) the poster wouldn't seem quite so brutal,

but it just seemed all wrong that in a city where the newspapers live

off rape crime stories and lots of women say they are afraid of the

threat of rape lots of the time. Here, the line between real life

and the fantasy of the film isn't solid enough to make the fantasy

seem entirely that -- just fantasy -- and therefore harmless.

The

poster really bothered me a lot, even though I think (though now I

wonder about that) that violent or sexual crime isn't driven by watching

violent or sexually graphic television or movies. All sorts of plots

drive x-rated movies -- and hey, it's just fantasy, right? Maybe in

some other place (Sweden?) the poster wouldn't seem quite so brutal,

but it just seemed all wrong that in a city where the newspapers live

off rape crime stories and lots of women say they are afraid of the

threat of rape lots of the time. Here, the line between real life

and the fantasy of the film isn't solid enough to make the fantasy

seem entirely that -- just fantasy -- and therefore harmless. Not

far from the cinema, a man with a prosthetic man was sitting with

a weighing scale. I wanted to take his photograph because he had removed

his prosthetic leg and had placed it next to him, as if it were for

sale too, but he looked sick and unwell so it didn't seem a very kind

thing to do. But the men nearby selling lemonade (poison in a glass)

said he wouldn't really mind if I took his picture and to take theirs

too. So I did and then felt obligated to have my weight taken as well.

The man with the missing leg announced to the world in general that

I had attained a weight of 62 kilograms (135 pounds), 4 kilos more

than when I last checked. It's because I don't get food poisoning

anymore.

Not

far from the cinema, a man with a prosthetic man was sitting with

a weighing scale. I wanted to take his photograph because he had removed

his prosthetic leg and had placed it next to him, as if it were for

sale too, but he looked sick and unwell so it didn't seem a very kind

thing to do. But the men nearby selling lemonade (poison in a glass)

said he wouldn't really mind if I took his picture and to take theirs

too. So I did and then felt obligated to have my weight taken as well.

The man with the missing leg announced to the world in general that

I had attained a weight of 62 kilograms (135 pounds), 4 kilos more

than when I last checked. It's because I don't get food poisoning

anymore. After

I went to Nangla Machi two weeks ago, I tried to make the rounds of

various government offices that deal with planning and housing. I

will say this for Indians (though I've probably said it somewhere

before) they know how to do bureaucracy. To be fair, some of the people

that I met at the municipal office known as the MCD were unexpectedly

helpful, certainly in terms of the time they gave me, but I can't

say I came away with much understanding of where the people in Nangla

were going to or who was calling the shots. I asked about the demolition

first, and I was told to go and talk to the land-owning agency. Who

would that be, I asked? The Delhi Development Authority.

After

I went to Nangla Machi two weeks ago, I tried to make the rounds of

various government offices that deal with planning and housing. I

will say this for Indians (though I've probably said it somewhere

before) they know how to do bureaucracy. To be fair, some of the people

that I met at the municipal office known as the MCD were unexpectedly

helpful, certainly in terms of the time they gave me, but I can't

say I came away with much understanding of where the people in Nangla

were going to or who was calling the shots. I asked about the demolition

first, and I was told to go and talk to the land-owning agency. Who

would that be, I asked? The Delhi Development Authority. I

then asked about the population of a neighborhood near mine and had

a conversation like this.

I

then asked about the population of a neighborhood near mine and had

a conversation like this. Everything

looked worse than before. The drains were fuller of stagnant water,

flies and mosquitoes were everywhere. You might think a slum doesn't

look like a very nice place to live it, but you probably haven't seen

a broken-down slum. There had been no light, no electricity for more

than two weeks. People there said lots of their children had fevers,

they feared malaria. They had been expecting a resolution at court

on April 4 but nothing had happened. April 17 -- Monday -- was the

next day movement was expected. But it wasn't clear to me whether

the action would be in court, as some said, or in the neighborhood

itself. Many said the bulldozers would come again to tear down the

pre-1998 houses that had been left standing.

Everything

looked worse than before. The drains were fuller of stagnant water,

flies and mosquitoes were everywhere. You might think a slum doesn't

look like a very nice place to live it, but you probably haven't seen

a broken-down slum. There had been no light, no electricity for more

than two weeks. People there said lots of their children had fevers,

they feared malaria. They had been expecting a resolution at court

on April 4 but nothing had happened. April 17 -- Monday -- was the

next day movement was expected. But it wasn't clear to me whether

the action would be in court, as some said, or in the neighborhood

itself. Many said the bulldozers would come again to tear down the

pre-1998 houses that had been left standing. On

a somewhat different note, I realize I was quite wrong to complain

so bitterly about my Pondicherry guesthouse's location next to a large

open drain and to regard it as apersonal flaw of the establishment

in question. In India, everything is located next to an open drain

and these drains have names, just as roads, markets and so on do.

I live next to one right now (the Shahdara Drain) and on balmy summer

evenings its fragrance wafts all through our building.

On

a somewhat different note, I realize I was quite wrong to complain

so bitterly about my Pondicherry guesthouse's location next to a large

open drain and to regard it as apersonal flaw of the establishment

in question. In India, everything is located next to an open drain

and these drains have names, just as roads, markets and so on do.

I live next to one right now (the Shahdara Drain) and on balmy summer

evenings its fragrance wafts all through our building.  This

past week, the newspapers were full of the shop sealings going on

all over Delhi as a result of a court order requiring commercial activity

in residential areas to be curtailed. But there was scarcely a mention

of Nangla Machi, a neighborhood on the western (central Delhi) side

of the Yamuna (not my side) along Ring Road as you head for the NH24

bridge to Noida and the wilds of East Delhi.

This

past week, the newspapers were full of the shop sealings going on

all over Delhi as a result of a court order requiring commercial activity

in residential areas to be curtailed. But there was scarcely a mention

of Nangla Machi, a neighborhood on the western (central Delhi) side

of the Yamuna (not my side) along Ring Road as you head for the NH24

bridge to Noida and the wilds of East Delhi. The

slum dwellers were protesting because bulldozers had come on Tuesday

morning and begun the process of tearing down their homes while the

men were away at work. The residents said they hadn't been warned

that this was going to happen -- they feared it and expected it at

some point, but not on that Tuesday. And no one -- – not the

residents, not the city slum department -- knew where they were suppose

to move to.

The

slum dwellers were protesting because bulldozers had come on Tuesday

morning and begun the process of tearing down their homes while the

men were away at work. The residents said they hadn't been warned

that this was going to happen -- they feared it and expected it at

some point, but not on that Tuesday. And no one -- – not the

residents, not the city slum department -- knew where they were suppose

to move to.